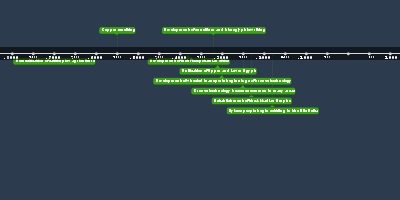

Roman Late Republic (jan 1, 133 BC – jan 1, 31 BC)

Description:

WHAT LED TO THE FALL OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC?“The wars of conquest created serious problems for the Romans. Ever-larger armies had to be recruited to defend Rome’s larger territory, with more extensive systems of administration and tax collection needed to support these.”

“The spoils of war seemed to many people to be unevenly distributed, with military contractors and those who collected taxes profiting greatly, while average soldiers gained little. These complex and explosive problems largely account for the turmoil of the late republic (133–27 B.C.E.) and the gradual transformation of government into one in which one man held the most power.”

THE COUNTRYSIDE AND LAND REFORMS

"Following a narrative of decline that began during the late republican period itself, historians traditionally saw the long-lasting foreign wars as devastating for the Roman countryside, with the prolonged fighting drawing men away from their farms for long periods, and the farms falling into wrack and ruin. There were not enough free men to keep the land under full cultivation, and women were not skilled enough to do so."

“This understanding of what was going on the countryside and its causes and consequences has been challenged in the twenty-first century by historians using archaeological, demographic, genetic, and other sources rather than primarily relying on the written works of elite men. Despite the losses due to foreign wars, the countryside was not depopulated, because the birthrate went up as families adjusted to meet the needs for agricultural labor over their life cycles. Families were able to maintain small and medium-sized family farms even when several of their men were away at war, with women or other male family members running them quite successfully…In this newer interpretation, landlessness was largely the result of overpopulation rather than simply a concentration of landholding into large estates, as when men returned from war there were too many people in the countryside. Many then did migrate to Rome, becoming urban poor who were unhappy with the way the Senate ran things. The city of Rome grew dramatically, but this did not leave the countryside empty.”

“[Tiberius Gracchus was] elected tribune in 133 B.C.E. Tiberius proposed that public land in the territories of Roman allies in Italy be redistributed to the poor of the city of Rome, and that the limit to the amount of land allowed to each individual set by the Licinian-Sextian laws be enforced. Although his reform enjoyed the support of some distinguished and popular members of the Senate, it angered those who had taken large tracts of public land for their own use, and also upset Rome’s allies, whose citizens were farming the land he proposed to give to Rome’s urban poor.”

“when [Tiberius Gracchus] sought re-election after his term was over, riots erupted among his opponents and supporters, and a group of senators beat Tiberius to death in cold blood. The death of Tiberius was the beginning of an era of political violence.

Although Tiberius was dead, his land bill became law, and his brother Gaius (GAY-uhs) Gracchus (153–121 B.C.E.) took up the cause. The name later given to the laws championed by the brothers, the Gracchi reforms”

POLITICAL VIOLENCE

"The death of Gaius brought little peace, and trouble came from two sources: the outbreak of new wars in the Mediterranean basin and further political unrest in Rome, problems that operated together to encourage the rise of military strongmen."

"Fighting was also a problem on Rome’s northern border, where two Germanic peoples, the Cimbri and Teutones, were moving into Gaul (present-day France) and later into northern Italy. After the Germans had defeated Roman armies sent to repel them, Marius as consul successfully led the campaign against them in 102 B.C.E., for which he was elected consul again, against the wishes of the Senate."

“Rome was dividing into two political factions, both of whom wanted political power; contemporaries termed these factions the populares and the optimates…In general the populares advocated for greater authority for the Citizens’ Assembly and the tribunes and spoke in language stressing the welfare of the Roman people, and the optimates upheld the leadership role of the Senate and spoke in the language of Roman traditions. Individual politicians shifted their rhetoric and tactics depending on the situation; however, both of these factions were represented in the Senate.”

"In 91 B.C.E. many Roman allies in the Italian peninsula rose up against Rome because they were expected to pay taxes and serve in the army but had no voice in political decisions because they were not full citizens. This revolt became known as the Social War, so named from the Latin word socius, or “ally.” Sulla’s armies gained a number of victories over the Italian allies, and Sulla gained prestige through his success in fighting them. In the end, however, the Senate agreed to give many allies Roman citizenship in order to end the fighting."

CIVIL WAR AND THE RISE OF JULIUS CAESAR

The history of the late republic is the story of power struggles among many famous Roman figures against a background of unrest at home and military campaigns abroad. This led to a series of bloody civil wars that raged from Spain across northern Africa to Egypt. Sulla’s political heirs were Pompey, Crassus, and Julius Caesar, all of them able military leaders and brilliant politicians. Pompey (106–48 B.C.E.) began a meteoric rise to power as a successful commander of troops for Sulla…Crassus (ca. 115–53 B.C.E.) also began his military career under Sulla and became the wealthiest man in Rome through buying and selling land…Pompey and Crassus then made an informal agreement with the populares in the Senate. Both were elected consuls in 70 B.C.E. and began to dismantle Sulla’s constitution and initiate economic and political reforms. They and the Senate moved too slowly for some people, however, and several politicians who had been losing out in the jockeying for power, especially Catiline (108–62 B.C.E.), planned a coup, attracting people to their cause with the promise of debt relief…”

“The man who cast the longest shadow over these troubled years was Julius Caesar (100–44 B.C.E.). Born of a noble family, he received an excellent education, which he furthered by studying in Greece with some of the most eminent teachers of the day. He had serious intellectual interests and immense literary ability… Caesar was a superb orator, and his personality and wit made him popular… Caesar was a military genius who knew how to win battles and turn victories into permanent gains. He was also a shrewd politician of unbridled ambition… He became a protégé of Crassus, who provided cash for Caesar’s needs… Caesar launched his military career in Spain, where his courage won the respect and affection of his troops.”

“the three [Pompey, Crassus, and Julius Caesar] concluded an informal political alliance later termed the First Triumvirate (trigh-UHM-veh-ruht). Crassus’s money helped Caesar be elected consul, and Pompey married Caesar’s daughter Julia. Crassus was appointed governor of Syria, Pompey of Hispania (present-day Spain), and Caesar of Gaul.”

“The First Triumvirate disintegrated. Crassus died in battle while trying to conquer Parthia, and Caesar and Pompey accused each other of treachery. Fearful of Caesar’s popularity and growing power, the Senate sided with Pompey and ordered Caesar to disband his army. He refused, and instead in 49 B.C.E. he crossed the Rubicon River in northern Italy — the boundary of his territorial command — with soldiers…Although their forces outnumbered Caesar’s, Pompey and the Senate fled Rome, and Caesar entered the city and took control without a fight.”

“In 48 B.C.E., despite being outnumbered, [Caesar] defeated Pompey and his army at the Battle of Pharsalus in central Greece. Pompey fled to Egypt, which was embroiled in a battle for control not between two generals but between a brother and a sister, Ptolemy XIII and Cleopatra VII (69–30 B.C.E.). Caesar followed Pompey to Egypt, Cleopatra allied herself with Caesar, and Caesar’s army defeated Ptolemy’s army, ending the power struggle. Pompey was assassinated in Egypt, Cleopatra and Caesar became lovers, and Caesar brought Cleopatra to Rome. Caesar put down a revolt against Roman control by the king of Pontus in northern Turkey, then won a major victory over Pompey’s army — now commanded by his sons — in Spain.”

“[Caesar’s] chief supporter and client in Rome, Mark Antony (83–30 B.C.E.), who was himself a military commander…”

Added to timeline:

Date:

jan 1, 133 BC

jan 1, 31 BC

~ 102 years