dec 25, 1959 - British Blues

Description:

American jazz and jazz-related popular music had intrigued the British since ragtime music by Scott Joplin reached England through published sheet music. During the early decades of the twentieth century, a number of American jazz soloists and groups toured Britain, as well as the rest of Europe, creating quite a furor over the new mu sic, which, in some ways, gained greater acceptance in Britain and Europe than in America, where it too often was considered the primitive product of an inferior people. The development of the recording industry, too, helped to bring American music to the attention of the rest of the world. Groups imitating those on the American recordings sprang up all over Europe, and jazz became an interna tional music with its roots in African American culture. American rock and roll became popular in England during the late fifties. Although some American perform ers did tour in Britain, the English soon produced their own soloists and groups who patterned themselves after various American originals. On the heels of Elvis Presley, Gene Vincent, and Eddie Cochran came their British imitators, Tommy Steele, Billy Fury, and Joe Brown. When American rhythm and blues and rockabilly styles were superseded by the blander, dance-oriented style pop ularized on "American Bandstand," some British fans turned to the pop rock of Cliff Richard and Marty Wilde. Those who could not relate to that pop style became disil lusioned with rock and abandoned it for the older, gutsier type of music in which fifties rock was rooted-the blues. British musician Chris Barber started a band in 1954 that played trad jazz, skiffie, and country blues at clubs in London. As Barber's following grew, musicians who had played with him left to form their own groups. By the early sixties, blues clubs had sprung up all over the city. Among the more successful bands were Cyril Davies Rhythm and Blues All-Stars (formed in the late fifties), Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies Blues Incorporated (formed in 1961), the Rolling Stones (formed in 1962), John Mayall's Blues breakers (formed in 1963), the Spencer Davis Rhythm and Blues Quartet (formed in 1963, later renamed the Spencer Davis Group), the Yardbirds (formed in 1963), and the Graham Bond Organisation (formed in 1963). In addition to making many cover recordings of American blues songs, these British groups wrote original material based on theblues style.

Most of the British blues covers were not sanitized and countrified versions of the blues originals, as were those made by white artists in America during the fifties. The British covers of the early sixties, although often not exact copies, were as close to the style and feel of the originals as they could get, including the use of bottlenecks and string-bending techniques on the guitar. Some of the covers added more interesting and active bass or lead guitar lines than were heard in the original recordings; the tempos varied, with some covers slightly faster than the originals and some slower; and at times some modifica tions were made in melodies . But the important point was that these covers did not involve changes in the basic character of the music. The British were not covering the blues in order to make commercial hits. They were play ing the blues out of a real love, respect, and enthusiasm for the music. Some of the groups did indeed go on to commercial success through more pop-oriented music, but even then their styles retained the influence of their earlier experience with the blues.

In the early fifties, Cyril Davies played banjo in a trad jazz band, but as he became more attracted to pure blues he concentrated on singing and playing the harp. With guitarist Alexis Korner, Davies formed the amplified blues group Blues Incorporated, which became the training ground for many blues-styled rock artists, including drummers Charlie Watts and Ginger Baker, singer Mick Jagger, and bassist Jack Bruce.

As a group that started out playing the blues, the Rolling Stones were exceptional in having stayed together for so long with so few membership changes. It was more typical for musicians of blues revival groups of the sixties to move from one band to another quite often. The blues was such a distinct musical style, with its own musical language and such well-established formal traditions, that it was very easy for musicians to walk on stage and perform with others with whom they had never worked before . Blues musicians improvised much of what they played, and as long as the improvisations followed the traditional twelve-bar har monic progression, or some variant of it, and as long as the musicians listened and were responsive to each other, what ever they played would fit together. Clearly, some combi nations of players worked better than others, but part of the joy of playing an improvised music such as the blues lay in the musical give-and-take among the musicians.

It was already mentioned that Blues Incorporated had frequent personnel changes, but an even more important group that functioned as a training ground for many a blues-rock musician was John Mayall's Bluesbreakers. The group was formed in 1963, and throughout its existence Mayall's singing and harp, guitar, and keyboard playing remained faithful to the blues tradition. Many of his Blues breakers left to form commercial rock groups, but their ex perience in playing the blues continued to influence their rock styles. Among the rock musicians who worked with the Bluesbreakers early in their careers were guitarists Eric Clap ton, Mick Taylor, and Peter Green; bassists John McVie, Jack Bruce, and Andy Fraser; and drummers Keef Hartley, Aynsley Dunbar, and Mick Fleetwood. John Mayall was sometimes called the Father of the British Blues because of the Bluesbreakers' importance to the blues revival.

Spencer Davis had sung and played both guitar and harp only as a hobby when he formed the Spencer Davis Rhythm and Blues Quartet, renamed the Spencer Davis Group, in 1963. Singer/guitarist/keyboardist Steve Winwood (born in 1948) and his brother Muff, a bassist, had played in trad jazz bands until they joined with Davis to form his blues band. The group's hit recordings "Gimme Some Lovin'" and 'Tm a Man" (both written by Steve Winwood) were made in 1967 and featured Steve Winwood as the singer. After the Spencer Davis Group broke up, Steven Winwood formed and recorded with Traffic, worked with Eric Clapton in Blind Faith, and later had a solo career in which he blended his blues background with jazz, folk, and even classical music.

Another British singer who patterned his vocal style after the sound of African American blues and rhythm and blues singers was Eric Burdon (born in 1941). He had been an art student in Newcastle upon Tyne until he became involved with the blues, the popularity of which had spread from London to his hometown in the north of England. He joined the Alan Price Combo as lead singer in 1962. Keyboard player Price and his group had been playing blues and rhythm and blues since 1958. With Burdon, the group became a popular club attraction with such a wild stage act that their fans began calling them the Animals, a name that stuck with them.

The Animals covered many American blues and rhythm and blues songs by Bo Diddley, John Lee Hooker, Fats Domino, and Chuck Berry. Not only was Burdon very good at imitating the tonal quality of the African American bluesmen , bur Alan Price did an impressive imitation of Bo Diddley's distinctive guitar style on his electric organ. The Animals also did nonblues songs, such as the American folk song "House of the Rising Sun" (1964), and with that and their original songs they became less a blues group and more a rock group with a style that was rooted in the blues. Another in the lineup of British blues bands was the Yardbirds, formed in London in 1963. Their lead guitarist, Anthony "Top" Topham, was replaced by Eric Clapton after the group had been together for only four months. The Yardbirds started out playing covers of American blues recordings and gained a following at some of London's blues clubs. When blues singer/harpist Sonny Boy Williamson No. 2 (Rice Miller) visited London in December 1963, he chose the Yardbirds to be his backup group. Only two months after those performances with Williamson, the Yardbirds were in a studio making a professional recording that led to a contract.

For the next year or so, the Yardbirds covered tunes by John Lee Hooker, Bo Diddley, Howlin' Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson, Willie Dixon, and Chuck Berry. But with the success of the Beatles and other British groups in America in 1964, most members of the group decided to stop playing the blues and try a more commercial style of music. The idea worked, and they achieved pop stardom in 1965 with "For Your Love," but they paid a price. Eric Clapton, the most blues-loving of the Yardbirds, refused to play guitar on any more pop recordings and left the group. To replace him, they first approached Jimmy Page (born in 1944). Page had earned a great deal of respect as a blues guitarist who could play almost any form of popular music, including the Yard birds' new commercial style, but he was so successful as a studio musician that he was not looking to join a group as a regular member. Tours would have caused him to lose stu dio jobs . Page recommended Jeff Beck (born in 1944), who had been playing with a rhythm and blues band called the Tridents , and shortly thereafter Beck joined the Yardbirds. Musically, Beck turned out to be a good choice. The Yardbirds were developing a commercial, psychedelic stage act, and Beck eagerly joined in by playing his guitar behind his head and experimenting with amplifier feedback. He also made frequent use of string bending, a technique that was not exclusively a part of the blues tradition; it was often employed on the sitar and other Indian stringed instruments. Beck even used his tech nique to imitate the sound of the sitar in the Yardbirds'

recording of "Heart Full of Soul" (1965).

In need of a new player, Beck asked Jimmy Page to join so the two of them could play lead guitar together. Page finally did join the Yardbirds, playing lead guitar alone in Beck's absence and sharing the spot when Beck was there. Beck finally quit the group in 1966 to form his own band, leaving Jimmy Page as the sole lead guitarist. When the other members left, Page put together a new group called the New Yardbirds. That group stayed to gether for a long and successful career as Led Zeppelin. Musically, Led Zeppelin was an important link between the blues and heavy metal.

Clapton remained closely tied to the blues for most of his career. Before joining the Yardbirds in 1963, he had played with two rhythm and blues groups, the Roosters and Casey Jones and the Engineers. Upon leaving the Yard birds, he joined John Mayall's Bluesbreakers and played with them fairly regularly for just over a year, from April 1965 to July 1966. The Bluesbreakers' frequent personnel changes gave Clapton an opportunity to work with a vari ety of blues musicians. He particularly liked Jack Bruce 's (born in 1943) bass playing, and when Ginger Baker (born in 1939) sat in on the drums one night, Clapton asked the two of them to join him to work as a trio. At that time, they intended to play the blues in small clubs and did not fore see the tremendous success they would have as Cream.The group made its debut in 1966 at the Windsor Festival in England, where they brought their blues-styled songs and brilliant improvisations at a high volume to a rock audience that was ripe for the experience.

Cream's 1968 recording of Robert Johnson 's "Cross Road Blues" (1936) was a successful link between the old country blues and the new blues-based rock. Although the members of Cream obviously loved the rough quality of Johnson's style, they did not copy it in their recording, which they retitled "Crossroads." Johnson had played with the rhythmic freedom out of which the blues form had developed (as was pointed out in the discussion and listening guide to Johnson's recording in Chapter 2) . Cream's more modern audience, however, required the sort of polish and formalism to which they had become accustomed. Cream was also made up of three very technically proficient instrumentalists, and where John son used his guitar primarily to accompany his singing, Cream displayed their talents through six all-instrumental choruses of the twelve-bar form. A listening guide to Cream's recording of "Crossroads" follows on page 128. The recording hit number twenty-eight on the American pop charts; it did not chart in England.

Other British covers of the late sixties included the Jeff Beck Group's recordings of Willie Dixon's "I Ain't Super stitious" and "You Shook Me"; Cream's recordings of Dixon's "Spoonful," Robert Johnson's "Four until Late," and Howlin' Wolfs "Sittin' on Top of the World"; and Led Zeppelin's recordings of Dixon's "I Can't Quit You Baby" and "You Shook Me." A comparison of any of these record ings with the original versions reveals that the late-sixties British blues groups remained less faithful to the old styles than their early-sixties predecessors had.

After just over two years together, Cream disbanded. They felt they had made the musical statement they had gotten together to make, and all three wanted to move on to other experiences. Clapton and Baker formed a new group with Traffic's keyboardist/singer Steve Winwood and Fam ily's bassist, Rich Grech. The new group, Blind Faith, was short-lived, putting out only one album, Blind Faith ( 1969). After Blind Faith broke up, Clapton worked with a va riety of groups for short periods of time, including Derek and the Dominos, a group that included American southern-rock guitarist Duane Allman. The name "Derek" was a combination of the names Duane and Eric, and the two guitarists shared lead guitar lines in much the same way that Allman and Dickey Betts had in Allman's own group, the Allman Brothers Band. Derek and the Dominos recorded "Layla" (1970), one of Clapton's great est musical and personal statements, inspired by his infat uation with Beatie George Harrison's wife, Pattie (whom Clapton later married and divorced). The lyrics to "Layla" included a quote from Robert Johnson's "Love in Vain." Personal depression led to a heroin habit that kept Eric Clapton from being an active performer during much of 1971 and 1972. He managed to kick the habit with the help of the Who's Pete Townshend, who organized and played with Clapton in The Rainbow Concert (January 13, 1973). The concert, which also featured guitarist Ron Wood, Steve Winwood, and Rick Grech, turned out to be Clapton's much-needed comeback. From that point on, Clapton worked as a soloist, with a variety of musicians serving as his backup band. In many ways, his later style became more commercial than he would ever have al lowed back in his Yardbird days, but the influence of the blues continued to color his music. His career hit a new peak when he was awarded six Grammys in 1993. An ad ditional Grammy was awarded to Clapton, this time for Best Traditional Blues Album, for From the Cradle, released in 1994. Clapton gave further tribute to "King of the Delta Blues," Robert Johnson, by recording his songs on Me and Mr. Johnson (2004).

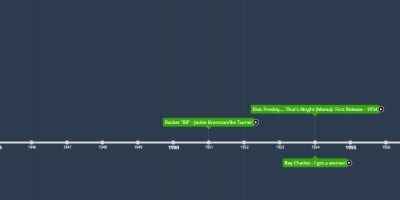

Added to timeline:

Date:

dec 25, 1959

Now

~ 64 years ago