Xerxes King of Persia 495 - 475 B.C.E. (23 ноя 495 г. до нашей эры – 12 март 475 г. до нашей эры)

Описание:

WATCHTOWER: AHASUERUSThe Ahasuerus of the book of Esther is believed to be Xerxes I, the son of the Persian king Darius the Great (Darius Hystaspis). Ahasuerus (Xerxes I) is shown as ruling over 127 jurisdictional districts, from India to Ethiopia. The city of Shushan was his capital during major portions of his rule.—Es 1:1, 2.

In the book of Esther the regnal years of this king apparently are counted from the coregency with his father Darius the Great. This would mean that Xerxes’ accession year was 496 B.C.E. and that his first regnal year was 495 B.C.E. (See PERSIA, PERSIANS.) In the third year of his reign, at a sumptuous banquet, he ordered lovely Queen Vashti to present herself and display her beauty to the people and princes. Her refusal caused his anger to flare up, and he dismissed her as his wife. (Es 1:3, 10-12, 19-21) In the seventh year of his reign he selected Esther, a Jewess, as his choice out of the many virgins brought in as prospects to replace Vashti. (Es 2:1-4, 16, 17) In the 12th year of his reign he allowed his prime minister Haman to use the king’s signet ring to sign a decree that would result in a genocidal destruction of the Jews. This scheme was thwarted by Esther and her cousin Mordecai, Haman was hanged, and a new decree was issued, allowing the Jews the right to fight their attackers.—Es 3:1-11; 7:9, 10; 8:3-14; 9:5-10.

Subsequently, “King Ahasuerus proceeded to lay forced labor upon the land and the isles of the sea.” (Es 10:1) This activity fits well with the pursuits of Xerxes, who completed much of the construction work his father Darius initiated at Persepolis.

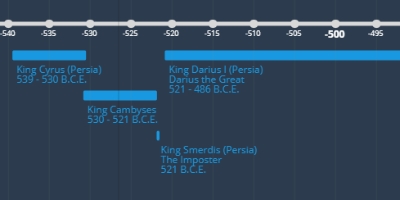

Xerxes I also appears to be the “fourth [king]” mentioned at Daniel 11:2, the three preceding ones being Cyrus the Great, Cambyses II, and Darius Hystaspis. While seven other kings followed Xerxes on the throne of the Persian Empire, Xerxes was the last Persian emperor to carry war into Greece, whose rise as the dominant world power is described in the verse immediately following.—Da 11:3.

__________________________________________________

WATCHTOWER: PERSIA, PERSIAN

Xerxes, Darius’ son, is evidently the king called Ahasuerus in the book of Esther. His actions also fit the description of the fourth Persian king, who would “rouse up everything against the kingdom of Greece.” (Da 11:2) Endeavoring to retaliate for the Persian defeat at Marathon, Xerxes launched massive forces against the Greek mainland in 480 B.C.E. Following a costly victory at Thermopylae and the destruction of Athens, his forces met defeat at Salamis and later at Plataea, causing Xerxes to return to Persia.

Xerxes’ reign was marked by certain administrative reforms and the completion of much of the construction work his father had initiated at Persepolis. (Compare Es 10:1, 2.) The Greek stories of the end of Xerxes’ reign revolve around marital difficulties, disorders in the harem, and a supposed dominance of Xerxes by certain of his courtiers. These accounts may reflect, though in a very confused and twisted way, some of the basic facts of the book of Esther, including the deposing of Queen Vashti and her replacement by Esther, as well as the ascension of Mordecai to a position of great authority in the realm. (Es 2:17; 10:3) According to secular accounts, Xerxes was assassinated by one of his courtiers.

...

There is solid evidence for a coregency of Xerxes with his father Darius. The Greek historian Herodotus (VII, 3) says: “Darius judged his [Xerxes’] plea [for kingship] to be just and declared him king. But to my thinking Xerxes would have been made king even without this advice.” This indicates that Xerxes was made king during the reign of his father Darius.

Evidence from Persian sources. A coregency of Xerxes with Darius can be seen especially from Persian bas-reliefs that have come to light. In Persepolis several bas-reliefs have been found that represent Xerxes standing behind his father’s throne, dressed in clothing identical to his father’s and with his head on the same level. This is unusual, since ordinarily the king’s head would be higher than all others. In A New Inscription of Xerxes From Persepolis (by Ernst E. Herzfeld, 1932) it is noted that both inscriptions and buildings found in Persepolis imply a coregency of Xerxes with his father Darius. On page 8 of his work Herzfeld wrote: “The peculiar tenor of Xerxes’ inscriptions at Persepolis, most of which do not distinguish between his own activity and that of his father, and the relation, just as peculiar, of their buildings, which it is impossible to allocate to either Darius or Xerxes individually, have always implied a kind of coregency of Xerxes. Moreover, two sculptures at Persepolis illustrate that relation.” With reference to one of these sculptures, Herzfeld pointed out: “Darius is represented, wearing all the royal attributes, enthroned on a high couch-platform supported by representatives of the various nations of his empire. Behind him in the relief, that is, in reality at his right, stands Xerxes with the same royal attributes, his left hand resting on the high back of the throne. That is a gesture that speaks clearly of more than mere successorship; it means coregency.”

As to a date for reliefs depicting Darius and Xerxes in that way, in Achaemenid Sculpture (Istanbul, 1974, p. 53), Ann Farkas states that “the reliefs might have been installed in the Treasury sometime during the building of the first addition, 494/493–492/491 B.C.; this certainly would have been the most convenient time to move such unwieldy pieces of stone. But whatever their date of removal to the Treasury, the sculptures were perhaps carved in the 490’s.”

Evidence from Babylonian sources. Evidence for Xerxes beginning a coregency with his father during the 490’s B.C.E. has been found at Babylon. Excavations there have unearthed a palace for Xerxes completed in 496 B.C.E. In this regard, A. T. Olmstead wrote in History of the Persian Empire (p. 215): “By October 23, 498, we learn that the house of the king’s son [that is, of Darius’ son, Xerxes] was in process of erection at Babylon; no doubt this is the Darius palace in the central section that we have already described. Two years later [in 496 B.C.E.], in a business document from near-by Borsippa, we have reference to the ‘new palace’ as already completed.”

Two unusual clay tablets may bear additional testimony to the coregency of Xerxes with Darius. One is a business text about hire of a building in the accession year of Xerxes. The tablet is dated in the first month of the year, Nisan. (A Catalogue of the Late Babylonian Tablets in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, by R. Campbell Thompson, London, 1927, p. 13, tablet designated A. 124) Another tablet bears the date “month of Ab(?), accession year of Xerxes.” Remarkably, this latter tablet does not attribute to Xerxes the title “king of Babylon, king of lands,” which was usual at that time.—Neubabylonische Rechts- und Verwaltungsurkunden übersetzt und erläutert, by M. San Nicolò and A. Ungnad, Leipzig, 1934, Vol. I, part 4, p. 544, tablet No. 634, designated VAT 4397.

These two tablets are puzzling. Ordinarily a king’s accession year begins after the death of his predecessor. However, there is evidence that Xerxes’ predecessor (Darius) lived until the seventh month of his final year, whereas these two documents from the accession year of Xerxes bear dates prior to the seventh month (one has the first month, the other the fifth). Therefore these documents do not relate to an accession period of Xerxes following the death of his father but indicate an accession year during his coregency with Darius. If that accession year was in 496 B.C.E., when the palace at Babylon for Xerxes had been completed, his first year as coregent would begin the following Nisan, in 495 B.C.E., and his 21st and final year would start in 475 B.C.E. In that case, Xerxes’ reign included 10 years of rule with Darius (from 496 to 486 B.C.E.) and 11 years of kingship by himself (from 486 to 475 B.C.E.).

On the other hand, historians are unanimous that the first regnal year of Darius II began in spring of 423 B.C.E. One Babylonian tablet indicates that in his accession year Darius II was already on the throne by the 4th day of the 11th month, that is, February 13, 423 B.C.E. (Babylonian Chronology, 626 B.C.–A.D. 75, by R. Parker and W. H. Dubberstein, 1971, p. 18) However, two tablets show that Artaxerxes continued to rule after the 11th month, the 4th day, of his 41st year. One is dated to the 11th month, the 17th day, of his 41st year. (p. 18) The other one is dated to the 12th month of his 41st year. (Old Testament and Semitic Studies, edited by Harper, Brown, and Moore, 1908, Vol. 1, p. 304, tablet No. 12, designated CBM, 5505) Therefore Artaxerxes was not succeeded in his 41st regnal year but ruled through its entirety. This indicates that Artaxerxes must have ruled more than 41 years and that his first regnal year therefore should not be counted as beginning in 464 B.C.E.

Evidence that Artaxerxes Longimanus ruled beyond his 41st year is found in a business document from Borsippa that is dated to the 50th year of Artaxerxes. (Catalogue of the Babylonian Tablets in the British Museum, Vol. VII: Tablets From Sippar 2, by E. Leichty and A. K. Grayson, 1987, p. 153; tablet designated B. M. 65494) One of the tablets connecting the end of Artaxerxes’ reign and the beginning of the reign of Darius II has the following date: “51st year, accession year, 12th month, day 20, Darius, king of lands.” (The Babylonian Expedition of the University of Pennsylvania, Series A: Cuneiform Texts, Vol. VIII, Part I, by Albert T. Clay, 1908, pp. 34, 83, and Plate 57, Tablet No. 127, designated CBM 12803) Since the first regnal year of Darius II was in 423 B.C.E., it means that the 51st year of Artaxerxes was in 424 B.C.E. and his first regnal year was in 474 B.C.E.

__________________________________________________

SECULAR HISTORY

Xerxes was Darius's son. He continued the war against the Greeks and continued building at Persepolis.

Xerxes, Darius’ son, is evidently the king called Ahasuerus in the book of Esther. His actions also fit the description of the fourth Persian king, who would “rouse up everything against the kingdom of Greece.” (Da 11:2) Endeavoring to retaliate for the Persian defeat at Marathon, Xerxes launched massive forces against the Greek mainland in 480 B.C.E. Following a costly victory at Thermopylae and the destruction of Athens, his forces met defeat at Salamis and later at Plataea, causing Xerxes to return to Persia.

Xerxes’ reign was marked by certain administrative reforms and the completion of much of the construction work his father had initiated at Persepolis. (Compare Es 10:1, 2.) The Greek stories of the end of Xerxes’ reign revolve around marital difficulties, disorders in the harem, and a supposed dominance of Xerxes by certain of his courtiers. These accounts may reflect, though in a very confused and twisted way, some of the basic facts of the book of Esther, including the deposing of Queen Vashti and her replacement by Esther, as well as the ascension of Mordecai to a position of great authority in the realm. (Es 2:17; 10:3) According to secular accounts, Xerxes was assassinated by one of his courtiers.

Добавлено на ленту времени:

Дата:

23 ноя 495 г. до нашей эры

12 март 475 г. до нашей эры

~ 20 years