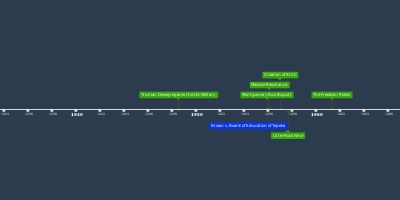

4 май 1961 г. - The Freedom Rides

Описание:

The Freedom Rides of 1961 were a way of exerting pressure on governments at all levels - local, state and federal - to enforce the right of African Americans to use interstate transportation unencumbered by segregation and segregationists.Just a year before, the US Supreme Court had reinforced "Irene Morgan v. the Commonwealth of Virginia" (1946) with "Boyton v. Virginia" (1960).

Consequently, both segregated interstate transportation and its associated facilities, such as terminals, waiting rooms, restaurants and restrooms, were prohibited by the US Constitution's Commerce Clause and the Interstate Commerce Act.

Civil rights leaders, such as the Congress of Racial Equality's (CORE) director, James Farmer, had high expectations of newly-inaugurated President John F Kennedy and his administration.

After tepid endorsement and enforcement of civil rights laws and rulings by the previous administration, it was hoped that Kennedy would focus on civil rights.

Testing the commitment of the new president, two mixed groups of African Americans and white passengers would travel from Washington, DC, to New Orleans, Louisiana, via the Deep South, passing through Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi.

One group of men and women would ride a Greyhound bus, the other would travel on Trailways.

Lack of compliance and overt defiance by cities and states would compel Kennedy to act.

As Farmer explained, "We put pressure and create a crisis (for federal leaders) and then they react".

The Freedom Readers expected threats, multiple arrests, and possible severe violence.

The concept of the rides was not universally appreciated by the civil rights community, with some believing that the rides would reverse the progress the NAACP had made in Mississippi.

Others, however, believed that the cautious ways of the 1950s had not garnered nationwide support, especially from the political leaders of the country.

A biracial contingent of thirteen Freedom Riders, six white and seven African American, began their trip on 4 May 1961, just two weeks after the failed Bay of Pigs effort to overthrow Fidel Castro, and as President Kennedy was preparing for his first meeting with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev.

On 14 May, as the first bus, the Greyhound, pulled up to the bus terminal in Anniston, Alabama, 30-50 men armed with sticks and metal bars surrounded the bus.

An incendiary bomb was thrown into the bys through a smashed rear window, causing a fire and filling the bus with smoke.

As the passengers streamed out, coughing and shielding their eyes, they were attacked and beaten until Eli Cowling, an undercover highway patrolmen, fired his weapon and threatened to kill the next person who attacked anyone.

At the Trailways bus terminal in Birmingham, a KKK mob of 30 men armed with baseball bats, chains and pipes first attacked reporters and news photographers, smashing cameras, before beating the Freedom Riders and several bystanders.

Photographs of the beaten Riders and stories of the Klan's mob attack were featured in major newspapers.

The Freedom Riders wanted to continue, but drivers from Greyhounds and Trailways refused to pilot buses with the Freedom Riders ob board, thus ending the first of the Freedom Rides.

The Freedom Rides did not end, although CORE no longer directed them.

Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) leaders John Lewis and Diane Nash immediately organized a second trip of 10 riders, many of them fellow students from Fisk College in Nashville, Tennessee.

President Kennedy called for a "cooling off period", but the Riders refused.

They finally had the attention of the White House and the press, both national and international.

The Freedom Riders were set to continue into Mississippi and invited King to join them.

The most nationally recognized fact of the movement declined for a second time, citing a need not to violate probation, but several Riders pointed out that they, too, were on probation.

As a result, King lost a significant amount of respect in the eyes of SNCC members, some Riders believing that the was afraid.

The Kennedy administration, fearing more violence when the bus entered Mississippi, made a deal with Mississippi Senator James Eastland: in exchange for a guarantee of protection from physical violence, the state could arrest the Riders for disturbing the peace and similar violations.

Consequently, the Riders were arrested, spending time in the notorious Parchman Prison.

As people around the country became aware of their fate, several hundred untrained and unsolicited Freedom Riders from across the United States travelled to Jackson, Mississippi, by plane, train and bus., eventually crowding the prison with over 300 Riders.

The Kennedy administration pressed the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) for a ruling.

On 22 September, the ICC issued a ban on segregation on interstate travel, which took effect on 1 November.

Many facilities were desegregated with little publicity in the succeeding months, the Kennedy administration threatening legal action to localities that disobeyed the order.

CORE reported that, by the end of 1962, segregation of interstate travel had ended.

The Freedom Rides achieved the specific goal of integrating interstate travel. They did not, however, achieve James Farmer's overall objective of obtaining overt, active support for civil rights from the federal government.

Support from the Kennedy administration was grudging, limited and slow.

Furthermore, the Freedom Rides accelerated a split between the civil rights movement itself: active confrontation and decentralized grassroots activism as expemplified by SNCC one hand, and the centralized, established leadership of the NAACP and the SCLC on the other.

The SCLC, formed just five years earlier in the wake of the Montgomery Bus boycott, its leaders and their families targets of bombing and other violence, was seen by many members of SNCC as too cautious to achieve significant change.

Добавлено на ленту времени:

Дата:

4 май 1961 г.

Сейчас

~ 64 г назад