9 h 55 m, 17 nov 2020 ano - CROCK OF GOLD A Few Rounds with Shane MacGowan THE TIMES Shane MacGowan on his new film

Descrição:

FROM WIKIPEDIA:Magnolia Pictures acquired the North American distribution rights. The North American premiere was on November 11, 2020 at DOC NYC followed by special screenings in theatres in the U.S. on December 1, 2020 before its general release on December 4, 2020.

The release in U.K. and Ireland cinemas by was delayed from November 20, 2020 to December 4, 2020 due to COVID-19.

FROM THE TIMES:

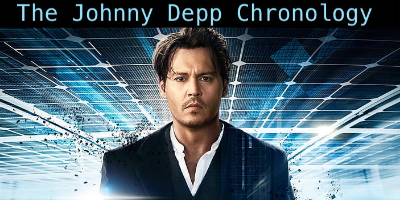

NOTE: this article makes it clear that Johnny Depp had withdrawn from promoting Crock of Gold due to the loss of the Uk Trial.

Shane MacGowan on his new film, Crock of Gold: ‘I’ve never liked being worshipped’

Shane MacGowan tells Will Hodgkinson about a revealing new film about him, produced by his old pal Johnny Depp

By Will Hodgkinson

In 2010 I pulled Shane MacGowan out of a ditch in Co Tipperary. It was six in the morning and we had spent the previous few hours in the astoundingly unkempt byre-dwelling that had been in his family for generations. The former lead singer of the Pogues, who revitalised Irish traditional music by infusing it with the spirit of punk, wanted to take me to a nearby copse that he claimed was inhabited by malevolent fairies. Unfortunately he had been drinking solidly for 24 hours, hence his disappearing, in a very real fashion, into a hole.

Once we got him out of the ditch MacGowan tottered down a country lane, where the place he called the Fairy Fort was just visible in the morning mist. “Only two people have ever gone in there,” he whispered reverentially. “The first one had to be taken straight to the lunatic asylum and the other came out with totally white hair.” Then he stuffed a clutch of banknotes into my hand and told me to take the two-hour taxi ride back to Dublin.

All of this came back in lurid detail while watching Crock of Gold, Julien Temple’s alternately hilarious and sobering portrait of one of the most charismatic and — against all laws of medicine — enduring figures in popular music. The film is produced by MacGowan’s friend Johnny Depp, so in awe of the singer that he slips into an Irish accent during scenes of the two drinking together, and it was made possible by MacGowan’s stoic partner of three decades, the writer Victoria Mary Clarke.

Through Beano-style animations and unseen footage, the film recreates a happy childhood in the Tipperary home. That was where relatives first introduced MacGowan to the joys of Guinness when he was a toddler and where an encounter with whiskey aged ten left him babbling incoherently to farmyard animals. From there it covers a miserable adolescence in London that was enlivened by the discovery of punk, and two decades of carousing around the world with the Pogues. It concludes with everyone from Sinéad O’Connor, to Bono, to the president of Ireland honouring MacGowan at his 60th birthday concert in 2018.

Along the way we get a sense of the man: enamoured of Irish mythology, literature and nationalism, maddeningly difficult to pin down, wary of praise. Decades of alcohol and drug abuse have left the author of such masterpieces as Fairytale of New York, censored or not, and A Pair of Brown Eyes with a severe case of writer’s block, and he has been in a wheelchair since breaking his pelvis in 2015. MacGowan doesn’t do interviews any more — he didn’t even grant one to Temple — but he has agreed to answer a few of my questions if Clarke puts them to him. I ask what he thought of the film.

“Julien Temple makes it look like I’m a miserable person,” he grouches.

“What are you, then?”

“I just react to other people. Johnny Depp is a brilliant guy, and he got Julien Temple because he has a reputation for making one of the first punk films [The Great Rock’n’Roll Swindle] — one that didn’t understand punk at all, but just showed people doing mad things. Johnny Depp understands punk. Julien Temple doesn’t.”

I can’t ask Depp, who says that he “fell in love with [MacGowan] the moment I met him and I’m still in love with him to this day”, to corroborate this because our interview has been scuppered by the loss of his highly publicised libel case against The Sun. Temple, however, confirms that working with MacGowan was anything but easy.

“I’ve known Shane since the punk years, and certainly didn’t know back then that he would become Mr Ireland,” says Temple, who first filmed MacGowan in the crowd of a Sex Pistols gig in London in 1976. “Initially I said no to making a film on him because I knew it would be mission impossible, but Johnny Depp got involved and asked me to reconsider. It was like David Attenborough filming the snow leopard: you had to set up the cameras and hope he’d appear. His cantankerousness pushed us into making a more interesting film.”

“There was animosity between Shane and Julien,” Clarke says. “Julien is not only English, but also upper-middle class, and he thought Shane would hate him for it. Shane told him, ‘No, I hate you because you’re a wanker.’ But Shane likes Johnny [Depp] because they share a respect for marginalised people. Johnny is way more polite than Shane, way more kind and patient, but they’re also similar in that if [they think] someone is a wanker — like Bob Geldof — they’ll say it.”

[Long Article continued via the links below]

Adicionado na linha do tempo:

Data:

9 h 55 m, 17 nov 2020 ano

Agora

~ 4 years and 11 months ago